Content from Writing Reproducible Python

Last updated on 2026-02-10 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is the difference between the standard library and third-party packages?

- How do I share a script so that it runs on someone else’s computer?

Objectives

- Import and use the

pathlibstandard library. - Identify when a script requires external dependencies (like

numpy). - Write a self-contained script that declares its own dependencies using inline metadata.

- Share a script which reproducibly handles

condadependencies alongside Python.

The Humble Script

Most research software starts as a single file. You have some data, you need to analyze it, and you write a sequence of commands to get the job done.

Let’s start by creating a script that generates some data and saves

it. We will use the standard library module pathlib to handle file paths safely across

operating systems (Windows/macOS/Linux).

PYTHON

import random

from pathlib import Path

# Define output directory

DATA_DIR = Path("data")

DATA_DIR.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

def generate_trajectory(n_steps=100):

print(f"Generating trajectory with {n_steps} steps...")

path = [0.0]

for _ in range(n_steps):

# Random walk step

step = random.uniform(-0.5, 0.5)

path.append(path[-1] + step)

return path

if __name__ == "__main__":

traj = generate_trajectory()

output_file = DATA_DIR / "trajectory.txt"

with open(output_file, "w") as f:

for point in traj:

f.write(f"{point}\n")

print(f"Saved to {output_file}")This script uses only Built-in modules (random, pathlib).

You can send this file to anyone with Python installed, and it will

run.

The Need for External Libraries

Standard Python is powerful, but for scientific work, we almost

always need the “Scientific Stack”: numpy,

pandas/polars, or matplotlib.

Let’s modify our script to calculate statistics using numpy.

PYTHON

import random

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np # new dependency!!

DATA_DIR = Path("data")

DATA_DIR.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

def generate_trajectory(n_steps=100):

# Use numpy for efficient array generation

steps = np.random.uniform(-0.5, 0.5, n_steps)

trajectory = np.cumsum(steps)

return trajectory

if __name__ == "__main__":

traj = generate_trajectory()

print(f"Mean position: {np.mean(traj):.4f}")

print(f"Std Dev: {np.std(traj):.4f}")The Dependency Problem

If you send this updated file to a colleague who just installed Python, what happens when they run it?

The Modern Solution: PEP 723 Metadata

Traditionally, you would send a requirements.txt file alongside your script, or

leave comments in the script, or try to add documentation in an

email.

But files get separated, and versions get desynchronized.

PEP

723 is a Python standard that allows you to embed

dependency information directly into the script file. Tools like uv (a fast Python package manager) can read this

header and automatically set up the environment for you.

We can add a special comment block at the top of our script:

PYTHON

# /// script

# requires-python = ">=3.11"

# dependencies = [

# "numpy",

# ]

# ///

import numpy as np

print("Hello I don't crash anymore..")

# ... rest of script ...Now, instead of manually installing numpy, you run the script using uv:

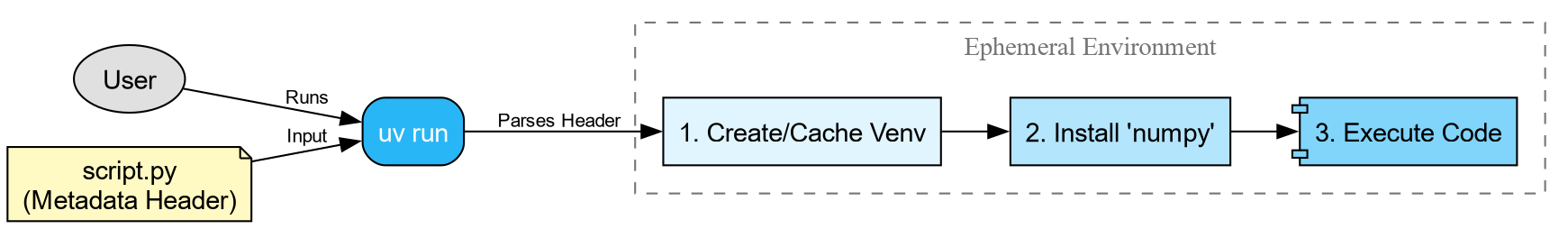

When you run this command:

-

uvreads the metadata block. - It creates a temporary, isolated virtual environment.

- It installs the specified version of

numpy. - It executes the script.

This guarantees that anyone with uv

installed can run your script immediately, without messing up their own

python environments.

Beyond Python: The pixibang

PEP 723 is fantastic for installable Python packages [fn:: most often this means things you can find on PyPI).

However, for scientific software, we often rely on compiled binaries

and libraries that are not Python packages—things like LAMMPS, GROMACS,

or eOn a server-client

tool for exploring the potential energy surfaces of atomistic

systems.

If your script needs to run a C++ binary, pip and uv cannot

help you easily. This is where pixi comes in.

pixi is a package manager

built on the conda ecosystem. It can

install Python packages and compiled binaries. We can

use a “pixibang”

script to effectively replicate the PEP 723 experience, but for the

entire system stack.

Example: Running minimizations with eOn and PET-MAD

Let’s write a script that drives a geometry minimization 1. This requires:

- Metatrain/Torch

- For the machine learning potential.

- rgpycrumbs

- For helper utilities.

- eOn Client

- The compiled C++ binary that actually performs the minimization.

First, we need to create the input geometry file pos.con in our directory:

BASH

cat << 'EOF' > pos.con

Generated by ASE

preBox_header_2

25.00 25.00 25.00

90.00 90.00 90.00

postBox_header_1

postBox_header_2

4

2 1 2 4

12.01 16.00 14.01 1.01

C

Coordinates of Component 1

11.04 11.77 12.50 0 0

12.03 10.88 12.50 0 1

O

Coordinates of Component 2

14.41 13.15 12.44 0 2

N

Coordinates of Component 3

13.44 13.86 12.46 0 3

12.50 14.51 12.49 0 4

H

Coordinates of Component 4

10.64 12.19 13.43 0 5

10.59 12.14 11.58 0 6

12.49 10.52 13.42 0 7

12.45 10.49 11.57 0 8

EOFNow, create the script eon_min.py. Note

the shebang line!

PYTHON

#!/usr/bin/env -S pixi exec --spec eon --spec uv -- uv run

# /// script

# requires-python = ">=3.11"

# dependencies = [

# "ase",

# "metatrain",

# "rgpycrumbs",

# ]

# ///

from pathlib import Path

import subprocess

from rgpycrumbs.eon.helpers import write_eon_config

from rgpycrumbs.run.jupyter import run_command_or_exit

repo_id = "lab-cosmo/upet"

tag = "v1.1.0"

url_path = f"models/pet-mad-s-{tag}.ckpt"

fname = Path(url_path.replace(".ckpt", ".pt"))

url = f"https://huggingface.co/{repo_id}/resolve/main/{url_path}"

fname.parent.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

subprocess.run(

[

"mtt",

"export",

url,

"-o",

fname,

],

check=True,

)

print(f"Successfully exported {fname}.")

min_settings = {

"Main": {"job": "minimization", "random_seed": 706253457},

"Potential": {"potential": "Metatomic"},

"Metatomic": {"model_path": fname.absolute()},

"Optimizer": {

"max_iterations": 2000,

"opt_method": "lbfgs",

"max_move": 0.5,

"converged_force": 0.01,

},

}

write_eon_config(".", min_settings)

run_command_or_exit(["eonclient"], capture=True, timeout=300)Make it executable and run it:

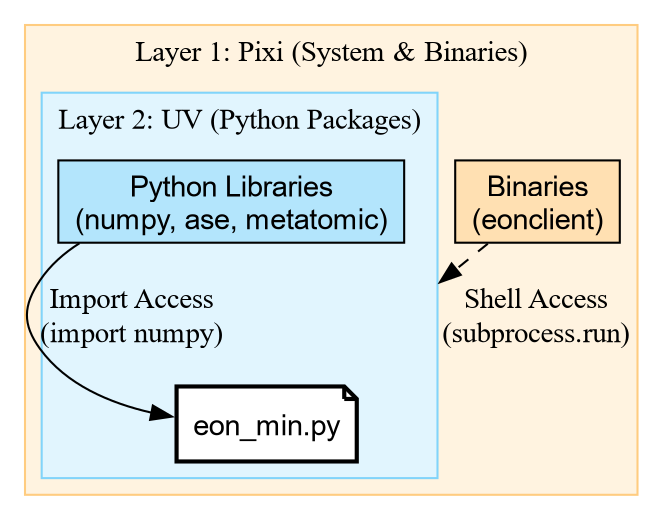

Unpacking the Shebang

The magic happens in this line: #!/usr/bin/env -S pixi exec --spec eon --spec uv -- uv run

This is a chain of tools:

-

pixi exec: Create an environment with

pixi. -

–spec eon: Explicitly request the

eonpackage (which contains the binaryeonclient). -

–spec uv: Explicitly request

uv. -

– uv run: Once the outer environment exists with

eOnanduv, it hands control over touv run. -

PEP 723:

uv runreads the script comments and installs the Python libraries (ase,rgpycrumbs).

This gives us the best of both worlds: pixi provides the

compiled binaries, and uv handles the fast Python

resolution.

The Result

When executed, the script downloads the model, exports it using metatrain, configures eOn, and runs the

binary.

[INFO] - Using best model from epoch None

[INFO] - Model exported to '.../models/pet-mad-s-v1.1.0.pt'

Successfully exported models/pet-mad-s-v1.1.0.pt.

Wrote eOn config to 'config.ini'

EON Client

VERSION: 01e09a5

...

[Matter] 0 0.00000e+00 1.30863e+00 -53.90300

[Matter] 1 1.46767e-02 6.40732e-01 -53.91548

...

[Matter] 51 1.56025e-03 9.85039e-03 -54.04262

Minimization converged within tolerence

Saving result to min.con

Final Energy: -54.04261779785156Challenge: The Pure Python Minimization

Create a script named ase_min.py that

performs the exact same minimization on pos.con, but uses the atomic simulation environment (ASE)

built-in LBFGS optimizer instead of

eOn.

Requirements:

- Do we need

pixi? Try using theuvshebang only (nopixi). - Reuse the model file we exported earlier (

models/pet-mad-s-v1.1.0.pt). - Compare the “User Time” of this script vs the EON script.

Hint: You will need the metatomic package to load the potential in

ASE.

PYTHON

# /// script

# requires-python = ">=3.11"

# dependencies = [

# "ase",

# "metatomic",

# "numpy",

# ]

# ///

from ase.io import read

from ase.optimize import LBFGS

from metatomic.torch.ase_calculator import MetatomicCalculator

def run_ase_min():

atoms = read("pos.con")

# Reuse the .pt file exported by the previous script

atoms.calc = MetatomicCalculator(

"models/pet-mad-s-v1.1.0.pt",

device="cpu"

)

# Setup Optimizer

print(f"Initial Energy: {atoms.get_potential_energy():.5f} eV")

opt = LBFGS(atoms, logfile="-") # Log to stdout

opt.run(fmax=0.01)

print(f"Final Energy: {atoms.get_potential_energy():.5f} eV")

if __name__ == "__main__":

run_ase_min()Initial Energy: -53.90300 eV

Step Time Energy fmax

....

LBFGS: 64 20:42:09 -54.042595 0.017080

LBFGS: 65 20:42:09 -54.042610 0.009133

Final Energy: -54.04261 eVSo we get the same result, but with more steps…

| Feature | EON Script (Pixi) | ASE Script (UV) |

| Shebang | pixi exec ... -- uv run |

uv run |

| Engine | C++ Binary (eonclient) |

Python Loop (LBFGS) |

| Dependencies | System + Python | Pure Python |

| Use Case | HPC / Heavy Simulations | Analysis / Prototyping |

While the Python version seems easier to setup, the eOn C++ client is often more performant, and equally trivial with the c.

- PEP 723 allows inline metadata for Python dependencies.

- Use uv to run single-file scripts with pure Python

requirements (

numpy,pandas). - Use Pixi when your script depends on system

libraries or compiled binaries (

eonclient,ffmpeg). - Combine them with a Pixibang (

pixi exec ... -- uv run) for fully reproducible, complex scientific workflows.

A subset of the Cookbook recipe for saddle point optimization↩︎

Content from Modules, Packages, and The Search Path

Last updated on 2026-02-10 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How does Python know where to find the libraries you import?

- What distinguishes a python “script” from a python “package”?

- What is an

__init__.pyfile?

Objectives

- Inspect the

sys.pathvariable to understand import resolution. - Differentiate between built-in modules, installed packages, and local code.

- Create a minimal local package structure.

From Scripts to Reusable Code

You have likely written Python scripts before: single files ending in

.py that perform a specific analysis or

task. While scripts are excellent for execution

(running a calculation once), they are often poor at facilitating

reuse.

Imagine you wrote a useful function to calculate the center of mass

of a molecule in analysis.py. A month

later, you start a new project and need that same function. You have two

options:

-

Copy and Paste: You copy the function into your new

script.

- Problem: If you find a bug in the original function, you have to remember to fix it in every copy you made.

- Importing: You tell Python to load the code from the original file.

Option 2 is the foundation of Python packaging. To do this effectively, we must first understand how Python finds the code you ask for.

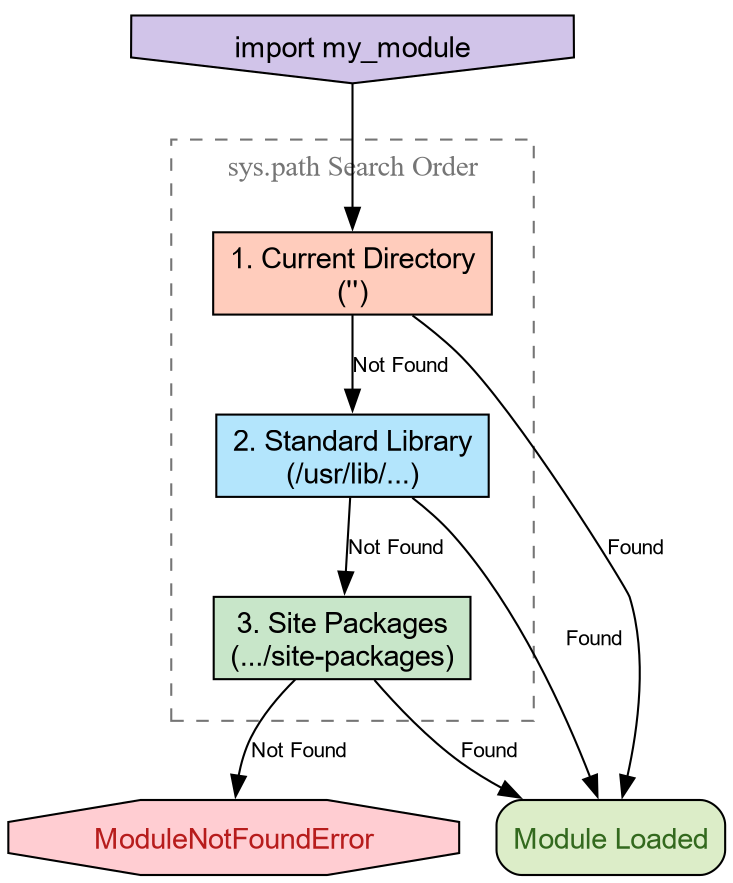

How Python Finds Code

When you type import numpy, Python does

not magically know where that code lives. It follows a deterministic

search procedure. We can see this procedure in action using the built-in

sys module.

PYTHON

['',

'/usr/lib/python314.zip',

'/usr/lib/python3.14',

'/usr/lib/python3.14/lib-dynload',

'/usr/lib/python3.14/site-packages']The variable sys.path is a list of

directory strings. When you import a module, Python scans these

directories in order. The first match wins.

-

The Empty String (’’): This represents the

current working directory. This is why you can always

import a

helper.pyfile if it is sitting right next to your script. -

Standard Library: Locations like

/usr/lib/python3.*contain built-ins likeos,math, andpathlib. -

Site Packages: Directories like

site-packagesordist-packagesare where tools likepip,conda, orpixiplace third-party libraries.

Python will import your local file instead of the

standard library math module.

Why? Because the current working directory

(represented by '' in sys.path) is usually at the top of the list. It

finds your math.py before scanning the

standard library paths. This is called “Shadowing” and is a common

source of bugs!

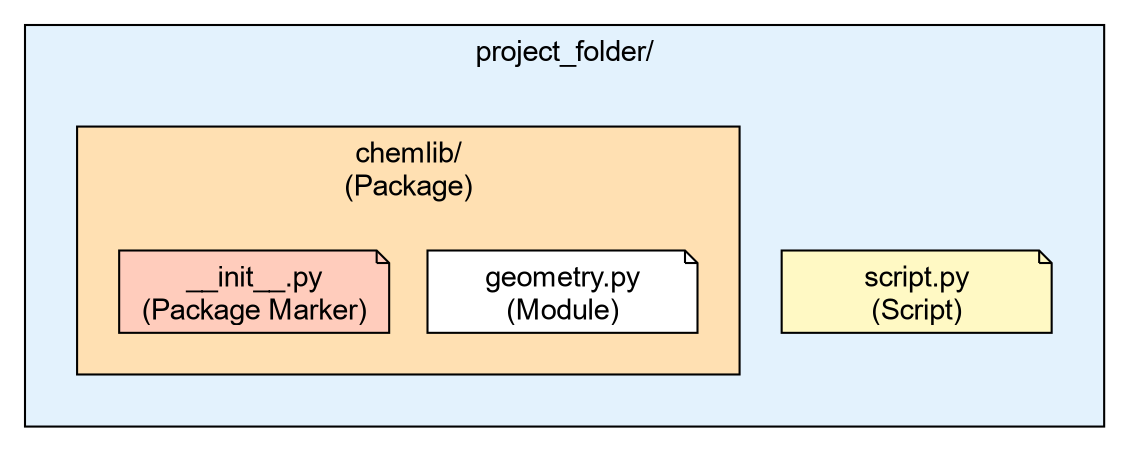

The Anatomy of a Package

- A Module

-

Is simply a single file ending in

.py. - A Package

-

Is a directory containing modules and a special file:

__init__.py.

Let’s create a very simple local package to handle some basic

chemistry geometry. We will call it chemlib.

Now, create a module inside this directory called geometry.py:

Your directory structure should look like this:

project_folder/

├── script.py

└── chemlib/

├── __init__.py

└── geometry.pyThe Role of __init__.py

The __init__.py file tells Python:

“Treat this directory as a package.” It is the first file executed when

you import the package. It can be empty, but it is often used to expose

functions to the top level.

Open `chemlib/_init__.py` and add:

Now, from the project_folder (the

parent directory), launch Python:

Loading chemlib package...

Calculating Center of Mass...

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0]The “It Works on My Machine” Problem

We have created a package, but it is fragile. It relies entirely on

the Current Working Directory being in sys.path.

Challenge: Moving Directories

- Exit your python session.

- Change your directory to go one level up (outside your project

folder):

cd .. - Start Python and try to run

import chemlib.

What happens and why?

Output:

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'chemlib'Reason: You moved out of the folder containing chemlib. Since the package is not installed in

the global site-packages, and the current

directory no longer contains it, Python’s search through sys.path fails to find it.

To solve this, we need a standard way to tell Python “This package exists, please add it to your search path permanently.” This is the job of Packaging and Installation.

-

sys.pathis the list of directories Python searches for imports. - The order of search is: Current Directory -> Standard Library -> Installed Packages.

- A Package is a directory containing an

__init__.pyfile. - Code that works locally because of the current directory will fail when shared unless properly installed.